Tom Carter's depressed about Africa:

Solving the problems of Africa exceeds the financial and political capabilities of any one nation, even the U.S. International gatherings of politicians and rock stars, no matter how well-meaning, have failed to produce anything meaningful. If the United Nations, founded to preserve international peace and stability, can't successfully plan and coordinate effective efforts to deal with Africa, then there may be no answer.Two approaches favored by leftists, rock-stars and the World Bank -- an uncommon alignment -- already failed. President Bush and Prime Minister Blair recently won agreement from G-8 (rich) nations to forgive $40 billion from 18 nations, most in sub-Sahara Africa. But debt relief provides little relief to the people of Africa, according to Richard Dowden of Britain's School of Oriental and African Studies, "Quite a lot of it [loans] wasn't used for what it was supposed to have been and quite a lot of it ended up back in private bank accounts in Switzerland and London."

Indeed, debt relief could actually extend poverty, through economic "moral hazard," "African states that receive total debt relief might be tempted to run up new debts and go into bankruptcy again ten years later." According to the Economist:

Debt relief, the argument goes, can only be a one-off event, a way of letting countries shrug off the excesses of the immediate post-colonial era; any hint that such relief might be available again would merely encourage bad governments to get themselves back into trouble.Debt relief essentially precludes further loans, "Africa desperately needs private investment and private capital. It is hard to fathom how debt forgiveness will improve the continent's credit rating in the financial capitals of the world." Moreover, debt relief for some might reduce the likelihood of sound governance elsewhere, says Der Spiegel:

Donor country generosity is giving a fatal signal. The message is that it isn't worth paying back loans, as at some point the international community will come along and take the burden anyway. "Those countries who, like us, have always paid their debts have been ignored, while those countries who have simply stopped paying are now getting all the attention," complains the Kenyan minister for planning, Peter Anyang Nyongo.For these and other reasons, even ordinary Africans are skeptical, such as Peter Kanans, a Kenyan coffee farmer:

Even if they cancel the debt, even if they give our governments aid money, ordinary Africans will not benefit. That money will only make the corrupt people richer and Africans international beggars for decades to come.Another approach, championed by the UN, the MSM, rock stars and liberal NGOs, is dramatically increased foreign aid for sub-Sahara Africa. The key word is increase, because rich nations give today:

(source: World Bank)

(source: World Bank)

Still, President Bush increased foreign aid to Africa; the G-8 as a whole promised an additional $50 billion by 2010 for sub-Sahara Africa. The UN's 2000 Millennium Declaration calls for further increases so as to halve global poverty by 2015.1 The money will help. But why hasn't it solved African poverty already? Will more money do the trick?

Almost certainly not; indeed, even the World Bank admits "there are legitimate doubts about whether the aid industry deserves credit [for poverty reduction]. Measurement of the effectiveness of aid has not yet produced some of the results that would really help." In fact, the evidence shows little correlation, says Cato's Marian Tupy:

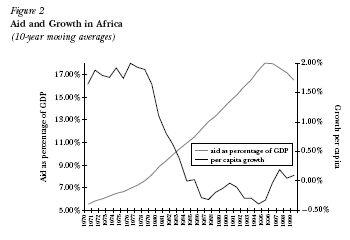

[B]etween 1960 and 2005, foreign aid worth more than $450 billion, inflation adjusted, poured into Africa. Result? Between 1975 and 2000, African gross domestic product (GDP) per capita declined at an average annual 0.59 percent rate. Over the same period, African GDP per capita fell from $1,770 in constant 1995 dollars adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP) to $1,479.

In contrast, South Asia performed much better. Between 1975 and 2000, South Asian GDP per capita grew at an average annual 2.94 percent. South Asian GDP per capita grew from $1,010 in constant 1995 dollars adjusted for PPP to $2,056. Yet, between 1975 and 2000, the per capita foreign aid South Asians received was 21 percent that received by Africa. The link between foreign aid and economic development seems quite tenuous.

(source: The Economist)

Scotsman reporter Alex Massie agrees in NRO, "Even allowing for different circumstances, that comparison is striking and ought to suggest that more aid is not necessarily the answer to African woes."

Worse yet, as Der Spiegel observes, "The suspicion is hard to avoid that aid, sometimes, paralyzes." Economic aid to poor nations tends to:

- destroy the tax system. Aid makes poor nation governments "dependent on their paymasters in the rich world, not their taxpayers at home. For every extra dollar of aid they are given, governments raise 28 cents less in tax, says Sanjeev Gupta, of the IMF."

- decimate local industries, because aid "undermine[s] the competitiveness of labor-intensive or exporting sectors."

- be mis-targed toward huge and splashy projects, like dam construction, that generate headlines and lucrative contracts for donor nation companies. Such funding tends to require abnormally high administrative overhead. Indeed, critics of the current system estimate that as little as 39 percent of foreign aid actually benefits the recipient country.

- be hoovered by corruption away from the intended and impoverished recipients. In a World Bank study of aid to Ugandan primary schools between 1991 and 1995, "only 13% of funds allocated for schools ever reached them. 'Ghost workers' gobbled up about a fifth of the money meant for teachers' salaries." According to Kathleen Millar writing in the WaPo, "Unless we lay the proper groundwork in Africa by helping states to institutionalize the rule of law, crime and corruption will undercut the best of intentions."

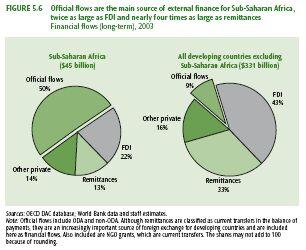

- crowd-out growth Already, half of sub-Sahara Africa's external financing is aid, not investment, as opposed to only nine percent for other developing nations:

(source: World Bank)

(source: World Bank)

But higher aid doesn't create prosperity; indeed, it seems to suppress growth: (source: William Easterly, Can Foreign Aid Buy Growth?, 17 J. Econ. Perspectives 28, 35 (2003).)

(source: William Easterly, Can Foreign Aid Buy Growth?, 17 J. Econ. Perspectives 28, 35 (2003).)

Never before have so many African intellectuals called for an end to the classic type of development aid. "Aid is not the solution," was the headline of the Kenyan newspaper The Standard. According to the paper, aid does not go directly to the people but to "bureaucratic structures."So is it hopeless? Is African poverty permanent? Is aid always ineffective? No. Nearly all know more effective approaches:

The worst thing about foreign aid, says the Monitor from Uganda, is that it prevents democratic development and urgently needed reforms. The paper also believes that aid stands in the way of long overdue and highly beneficial transparency in society.

- Good governance: Africa is rich in natural resources, far more so than East Asian tigers, such as Korea, that escaped poverty two decades ago. Africa has valuable human resources as well. The problem is a poverty of good policy, as P.J. O'Rourke once quipped:

The African relief fad serves to distract from the real issues. There is famine in Ethiopia, Chad, Sudan and areas of Mozambique. All of these countries are involved in pointless civil wars. There are pockets of famine in Mauritania, Niger and Mali - the result of desertification caused mostly by idiot agricultural policies. African famine is not a visitation of fate. It is largely man-made, and the men who made it are largely Africans.

Even the UN recognizes that poverty reduction depends on improving African politics and politicians:Success in meeting these objectives depends, inter alia, on good governance within each country. It also depends on good governance at the international level and on transparency in the financial, monetary and trading systems. We are committed to an open, equitable, rule-based, predictable and non-discriminatory multilateral trading and financial system.

Probably the best known proposed reform also could be the most effective: establishing clear title to land. The idea, most commonly associated with Peruvian economist Hernando De Soto, is simple:[W]e are now beginning to realize that you cannot carry out macroeconomic reforms on sand. Capitalism requires the bedrock of the rule of law, beginning with that of property. This is because the property system is much more than ownership: it is in fact the hidden architecture that organizes the market economy in every Western nation. What the property system accomplishes is so central to capitalism that developed nations have come to take its success for granted; indeed even most property experts are unsure about the connections between property systems and the creation of capital. Yet these connections exist. Without them, buildings and land cannot be used to guarantee credit or contracts. Ownership of businesses cannot be divided and represented in shares that investors can buy. In fact, without property law, capital itself - the instrument that allows people to leverage their assets and their transactions - is impossible to create: the instruments that store and transfer value, such as shares of corporate stock, patent rights, promissory notes, bills of exchange, bonds, etc., are all determined by the architecture of legal relationships with which a property system is built. And the problem is that 80 percent of the population of developing and former communist nations do not have legal property rights over their assets, whether it be homes, businesses or intellectual creations.

Moeletsi Mbeki, brother of South African President Thabo Mbeki, recently agreed in the Wall Street Journal:Future development in Africa requires a new type of democracy -- one that empowers not just the political elite but private-sector producers as well. It is necessary that peasants, who constitute the core of the private sector, become the real owners of their primary asset: land.

In other words -- whisper it -- good culture reduces poverty.

Private ownership of land would not only generate wealth but help to check rampant deforestation and accelerating desertification. The so-called communal land tenure system, which is really state ownership of land, ought to be abolished. Moreover, peasants need direct access to world markets. The producers must be able to auction their own cash crops rather than be forced to sell them to state-controlled marketing boards. - Small is beautiful: Huge projects seldom work, both because any benefits often are only regional and because large funding normally flows through corrupt governments. This suggests future projects be targeted toward small, even individual scale, initiatives, as Hartland Institute senior editor S. T. Karnick argues:

Government-to-government aid and NGO-to-government aid have proven ineffective. There can be no doubt of that. . .

This idea has been proven, at home and abroad, in the form of micro-loans, often designed to stimulate in-home production by women.

One excellent proposal is to make the World Bank a true bank, one that allows private organizations in developing nations to draw on accounts that will enable them to implement individualized projects covering a wide variety of constructive activities that give aid where it will do the most good, such as in construction of hospitals, water treatment, malaria prevention, agricultural technology, building of roads (a critical need in many African countries), literacy, immunization, AIDS prevention and treatment (including unbiased research into the causes of Africa's high incidence of the disease), and much, much more.

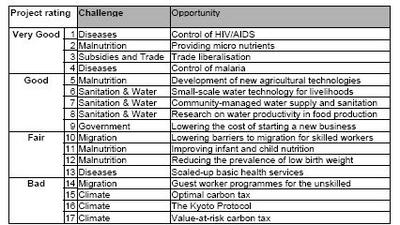

And there's new-found agreement on which aid provides the most benefits. For analysts such as Jeffery Sachs and Bjørn Lomborg, the best aid is the simplest. Attempting to quantify aid's costs and benefits, Lomborg organized a group called the Copenhagen Consensus, which ranked 17 projects in decreasing order of desirability: (source: Copenhagen Consensus final report)

(source: Copenhagen Consensus final report)

The Economist summarized how Lomborg's group would

spend appropriately:A large chunk was earmarked for HIV/AIDS prevention; some to combat malaria and malnutrition. The projects backed in Copenhagen demand relatively little of the governments that would have to implement them, and thus reflect one of the key lessons that have been learned from the many mistakes donors have made over the years.2

Better the "quick win" than protracted concrete pouring. - Market-oriented projects: Despite the bleatings of (redundant, I know) left-over communists and rock stars ("The economic theory of Live 8 was captured by columnist Anne Applebaum: "millionaire rapper Snoop Dogg shouts that 'there's a lot of rich people in the world and a lot of them are just selfish!'"), the Robin Hood policies of the past won't work. According to Robert Lucas, Economics Professor at the University of Chicago:

[O]f the vast increase in the well-being of hundreds of millions of people that has occurred in the 200-year course of the industrial revolution to date, virtually none of it can be attributed to the direct redistribution of resources from rich to poor. The potential for improving the lives of poor people by finding different ways of distributing current production is nothing compared to the apparently limitless potential of increasing production.

Put simpler, the key to reducing poverty is economic growth. Aid rarely buys growth. According to the Blair government,[W]e can finally see a growing consensus that true economic expansion requires a robust private sector. Governments need revenues from taxes and royalties in order to provide the services that underpin development. Foreign assistance can help, but at the end of the day cannot fulfill the requirement. Only private investors can produce the commodities and value-added goods that will finance development.

- Trade not aid: A corollary to the above is that commerce is better than charity. It is axiomatic that a free market exchange benefits both parties, while income redistribution is only a zero-sum game. So the best way to help Africa is to buy African. Yet, here the West has been both stingy and short-sighted, as Robert Mayer writes:

[T]he majority of Africans are small-scale farmers living on less than two dollars a day. In order to make free trade with Africa work, therefore ensuring its prosperity and democratization, the United States and Europe need to deal blows to a more covert enemy: agricultural subsidies. Artificially lowered prices in the West prevent their produce from entering the market, trapping them in a fake poverty with very real effects. When the G8 met in Scotland, they promised to cut deep into these subsidies; however, no timeline has been set and Africans are doubtful that one ever will be.

The consequences of lingering tariff barriers, particularly in textiles and farming, are astonishing, says European Union trade commissioner Peter Mandelson:Africa's share of global trade is falling. If we could only succeed in reversing that decline, the benefits for Africans would be enormous. A 1 per cent increase in Africa's share of global trade would deliver seven times more income every year than the continent currently receives in aid.

The best hope of success would be a program combining all the above elements. Such a project exists--thanks to President Bush's Millennium Challenge Corporation, authorized in 2003. The MCC's mission includes:

Reduce Poverty through Economic Growth: The MCC will focus specifically on promoting sustainable economic growth that reduces poverty through investments in areas such as agriculture, education, private sector development, and capacity building.The MCC uses publicly available statistics to rank potential aid recipients, and encourages those with sufficient transparency and legal stability to seek project-specific aid funding. After a slow, but optimistic beginning, the MCC has previously signed "compacts" with four nations, two of them (Cape Verde and Madagascar) in Africa, and recently approved $20 million of funding for Senegal and Burkina Faso. For the most part, the MCC program has escaped the media's attention.

Reward Good Policy: Using objective indicators, countries will be selected to receive assistance based on their performance in governing justly, investing their citizens, and encouraging economic freedom.

Free money is an ephemeral and incomplete answer. Aid remains essential in emergencies, but long-term reductions in African poverty await the transformation that lessened poverty in the West beginning four centuries ago and in Asia over the past half-century: capitalism and the rule of law.

More:

Dr. Hans H.J. Labohm in Tech Central:

[A]id can also have more pervasive unintended adverse effects on economic policy and public sector management. In this context the authors refer to Milton Friedman, who has argued that because most aid goes to governments, it tends "to strengthen the role of the government sector in general economic activity relative to the private sector". Aid is commonly used for patronage purposes, by subsidizing employment in the public sector, or in state-operated enterprises, as foreign aid can provide funds for government to undertake investments that would otherwise be made by private investors.____________

In Tanzania, for example, large and rising aid levels in the 1970s and 1980s helped sustain large government subsidies to state-owned enterprises. As high aid levels increase the rents available to those controlling the government, resources devoted to obtaining political influence increase; thus, as Peter Bauer has noted, "a pervasive consequence of aid has been to promote or exacerbate the politicization of life in aid receiving countries". In extreme cases, aid may even encourage coup attempts and political instability, by making control of the government and aid receipts a more valuable prize, with adverse effects for the security of property rights.

1 Unsurprisingly the UN Declaration is "Christmas-treed" with unproven exterania that likely hinders poverty reduction, including vows to: "free all of humanity, and above all our children and grandchildren, from the threat of living on a planet irredeemably spoilt by human activities, and whose resources would no longer be sufficient for their needs" and to "eliminate the increasing acts of racism and xenophobia in many societies and to promote greater harmony and tolerance in all societies."

2 Effective aid also requires donor nations to discard erroneous pre-conceived notions. For example, decreasing class size below 50 students (i.e., increasing the teacher student ratio) impoverishes other more effective educational reforms without "measurable impact on test scores."

5 comments:

Carl,

I am not always in agreement with your politics, but your article regarding Africa lays out a better plan for its development than the debt forgiveness that was recently provided by the G-8. Perhaps they (the G-8) should hire you as a consultant. To your 4-point plan to help develop the most underdeveloped continent on the planet, I will add this one small piece of vital insight - provide an education system that will create "confidence" in your 4 points. The American experiment is only 229 years old, and during that short period, it towers above every other country in the world with regards to economics; political, moral and military leadership; international capital markets; advanced research and development; leading edge technical education; the aerospace industry; international communications; high-tech weapons industry, etc., etc., etc. This experiment has only worked because the men and women, who participate in the system, have confidence that it works. I read Ayn Rands "Atlas Shrugged" years ago, and although she has no place for government in her fictional society and philosophy, (which I disagree with) her book demonstrates how a free market system will only work when faith/confidence and your four principles are applied.

America proves that free markets work, and if Africa as a continent is ever going to participate in the free market system, it must migrate away from its tribalistic, land-grabbing mentality to a society that embraces democratic ideals. And it won't hurt if the Western nations begin building factories on the continent that produces goods for the international community; of course, however, only after private property becomes more than a notion. This would be a better jump start than debt relief.

David

Carl, this post is among the best I've ever read on a blog. I linked to it in a post, and I think anyone interested in the future of Africa would do well to read it.

One of the reasons for my pessimism about the possibility of finding practical answers to the problems of Africa is embedded in everything written about the subject. Democracy, better governance, and respect for the rule of law are prerequisites, of course, but there is little evidence that the countries of Africa are capable of achieving those goals and maintaining them. More trade and commerce, yes, but developed countries, particularly including the U.S. and most importantly the EU and France in particular, aren't interested in reducing subsidies, especially to agriculture, and trade barriers as would be necessary. The Millennium Challenge initiative, despite the petty nitpicking of opponents of the Bush Administration, is the best idea yet advanced, but it won't work if the countries of Africa can't meet the criteria, and that seems likely.

As long as Africans can't meet even minimal standards and developed countries won't take the painful steps necessary to help develop trade and commerce, how can anyone be optimistic? I think cynical politicians and idiot do-gooders will have their way, and we will do little more than throw more money at the problem.

I generally agree that the suggestions of the Copenhagen Consensus, including the priorities, are logical, in the context of conventional thinking. However, the three climate suggestions seem more a sop to western political sensitivities than anything else. And in reality, the Copenhagen Consensus seems to be little more than an attempt to validate failed approaches of the past.

(This comment is cross-posted at The Answer for Africa.)

I agree! This might all be summed up by the old adage: "Give me a fish and I will eat for a day. Teach me to fish and I eat for a lifetime." But, as usual, Carl gives the stats and resources to back it up.

I like the comment on the need for educational reform as well. How else do you learn to fish? Finally, kudos to Carl for his reference to Hernando de Soto! Indeed, it points out that Carl's analysis applies to many more places than Africa. Even Iraq?

But there must be a reasonable transition that still leaves some fish to eat today while things improve. "Going cold turkey" just doesn't fit my metaphor.

That was some seriously exemplary blogging!

Thanks, all, for the praise. I've been a De Soto fan forever; I'm crushed each year he doesn't win the Noble. Given the appalling results of communal farming in Russia, China and elsewhere, and the widespread understanding that growth and poverty reduction can best come from below, De Soto's program should be top priority.

Tom, the Copenhagen list wasn't intended as exclusive. There's other programs listed on their web site; they chose to rank only those 17, probably to make the point that providing potable water is cheaper and more effective than changing the weather.

Pedro: I admit to little (and 15 years old) experience in sub-Sahara Africa (apart from South Africa). But back then I observed a stunted work ethic similar to some parts of pre-1990s Eastern Europe. After two generations where labor often netted little, some jump-start might help Africa.

Having saved India, extending the "Green Revolution" is a logical start. One ideal approach would combine money for higher-yield GM seeds for farmers and help in creating a cadre of regular middlemen to transport and distribute agriculture to city stores. Too bad the EU's scare-tactics suppressed such a system.

Post a Comment