Last week at National Review's The Corner, Jonah Goldberg posted a reader's email:

Jonah,I noted the question in an addendum to a healthcare article posted on August 3rd, pointing to two answers: one, partially anecdotal, in a two-year-old post, another in chart form in that same early-August post:

I'm a cancer survivor who was diagnosed in Germany. After two months in the limbo that is Germany's national health care system, I realized it would probably kill me so I returned to the U.S. for treatment. My chemotherapy started on the same day I saw my oncologist in New Jersey. Eleven years later and I'm still here. I wonder what the survival rates are in the UK?

source: Daniele Capezzone, president of the productivity committee of the Italian Chamber of Deputies, via Carpe Diem

Today's Telegraph (U.K.) supplies additional evidence:

Cancer survival rates in Britain are among the lowest in Europe, according to the most comprehensive analysis of the issue yet produced.Accompanying the article was this chart:

England is on a par with Poland despite the NHS spending three times more on health care.

Survival rates are based on the number of patients who are alive five years after diagnosis and researchers found that, for women, England was the fifth worst in a league of 22 countries. Scotland came bottom. Cancer experts blamed late diagnosis and long waiting lists. . .

A second article, which looked at 2.7 million patients diagnosed between 1995 and 1999, found that countries that spent the most on health per capita per year had better survival rates.

Britain was the exception. Despite spending up to £1,500 on health per person per year, it recorded similar survival rates for Hodgkin's disease and lung cancer as Poland, which spends a third of that amount.

source: The Telegraph

via Reason

Somehow, bad America has higher survivor rates.

I'm aware of studies and stories to the contrary. But those findings are flawed:

- Patient surveys aren't the most probative: Much of the data downgrading U.S. healthcare comes from surveys of current or former patients, including the Commonwealth Fund study. Surveys have some value--but also tend to reflect national pride and socialist self promotion. For individuals, free healthcare is great--but over-used, tax-funded free goods are a disaster for society.

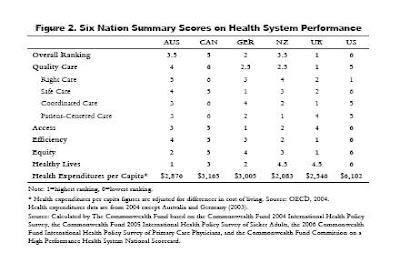

- What's the question: What you get out of a survey depends on what you put in. Cross-country statistics often track health care equity and access as values equally weighted with effectiveness. That makes overall U.S. rankings tumble: "The U.S. ranks a clear last on all measures of equity." But in a sense, such an approach assumes a socialized-medicine or -insurance model. Rating access and equity on par with effectiveness essentially makes universality twice as significant as curing the sick.

- Culture matters: Some studies include suicide rates in comparative health rankings--although national healthcare and/or insurance have next to nothing to do with trans-national variations reflecting different cultures. The freedom to keep firearms is more central to America, and -- because that variable is indenpendent of health care organization -- deaths by suicide has no place when comparing national healthcare delivery systems. Similarly, although it points toward the opposite result, the study's cross-national mortality data lowers U.S. healthcare rankings because the Supreme Court decided the Constitution forbade discrimination on alieanage when providing public assistance. So there's another independent variable -- we treat tons of illegal immigrants, a complication often excluded on the Continent. Direct comparisons are of little value, though they remind Hate-America-Firsters that our systems has some significant challenges not present to the same degree elsewhere. So, again, be careful what's measured in cross cultural health care rankings.

- Healing should be highest: Isn't the question which nation, and which system, provides the best care? I think so too, but the studies that fault America downplay such data, relegating "curing the sick" to a small part of overall effectiveness, as shown by this summary chart:

source: 2007 Commonwealth Comparison, page 5

Note that the U.S. ranks first in "right care" but next-to-last in "quality care." Why the difference? The Commonwealth authors explain:The indicators of quality were grouped into four categories: right (or effective) care, safe care, coordinated care, and patient-centered care. Compared with the other five countries, the U.S. fares best on provision and receipt of preventive care, a dimension of "right care." However, its low scores on chronic care management and safe, coordinated, and patient-centered care pull its overall quality score down. Other countries are further along than the U.S. in using information technology and a team approach to manage chronic conditions and coordinate care. Information systems in countries like Germany, New Zealand, and the U.K. enhance the ability of physicians to identify and monitor patients with chronic conditions. Such systems also make it easy for physicians to print out medication lists, including those prescribed by other physicians.

Got that? America might cure you, but Germany has automated drug charts. Which, on average, keeps you alive longer? - Good Doctor Godot: Finally, the Commenwealth's study seems to have shrunk Canada's paitient wait times about 90 percent.

I've always answered with this hypothetical: "You've just been diagnosed with cancer, and must choose medical treatment in one of two places: 1) the best hospital in Cuba; or 2) the Mayo Clinic. Do you buy an airline ticket to Havana or Rochester, Minnesota?"The U.K.'s closer to Havana than Harvard Med.. The U.S. isn't free--still, it's cheaper and more universal than claimed--and, as the Telegraph recognizes, it works--lowering survival risks desite increasing polyglot immigration that votes with its health-care dollars.

MORE:

The current Weekly Standard "is confident John Edwards will reject Castro's health care system--the instant he learns that you can't sue doctors in Cuba."

MORE & MORE:

In the Atlantic Megan McCardle explores The morality of health care finance. And tag-team bloggers Jamila Akil, Bruce McQuain and Radley Balko plus two California physicians rebut the assertion that America's assertedly high fetal mortality rate proves private healthcare and insurance has failed.

MORE3:

According to the World Health Organization's 2003 investigation into global health statistic methodology, Health Systems Performance Assessment: Debates, Methods and Empiricism, and in particular, the section on The Americas (page 29):

Unlike the comparison of the performance of the health system of a country with itself over time, the comparability of the performance of health systems between countries was viewed as something desirable, but difficult to carry out for technical and political reasons. . .(via Assistant Village Idiot)

The three dimensions of evaluation utilized in The World Health Report 2000 were discussed. . . The current concept of “responsiveness” encompasses some dimensions of quality of care, but deals only with the demand side. It does not take into account, for example, the technical quality of the supply side. It does not include direct measures of the degree of response to health-seeking behaviours of the population or of user satisfaction, nor does it consider cultural variability among countries and within the same country.

[Moreover], the concept and measure of “fair financing” were evaluated. It was decided that these concentrate exclusively on one side of the problem, the share of household expenditures devoted to health. They do not take into account the effect of public expenditure in public health and personal care. They do not permit the assessment of how progressive or regressive the financing of the health system is, and consequently do not refer to the full spectrum of financial protection with respect to health.

5 comments:

As far as automated charts goes, the number one stumbling block is HIPPA. That is a government program designed to provide absolute identity security in all medical record related ducumentation.

Computers can always be hacked. In some hospitals, this goes so far as to prevent patient names from being posted on ward room charts and from even being placed on the cover if patient medical charts.

Allah help the ward staff where two patients have the same or similar names.

This stuff is great. I've just been discussing this entire issue with a friend. I simply link to your articles.

I second sr's comment.

There is a psychological benefit to believing that you have free health care backing you up as life's vicissitudes come your way. People "feel" good about their already-provided care when they are not using it. It provides comfort.

While that can in itself be a good thing, you will notice that the illusion of quality care would provide the same benefit. Thus, a government only has to convince its citizens that their health care is "good enough" or "better than the other guy's" to achieve the feeling of security.

How the citizens fare once they are sick, not how positive they feel when they are well, is the test of the system.

Nice piece, Carl. Been looking for this sort of thing to combat the viewers of Sicko.

Thanks, all, for the kind words, but in this instance, it's not wholly warranted. I've been tied up with paying work and short on blog time. Even after editing -- I swear I wasn't drunk blogging Friday night, just tired -- I'm not happy about the writing. So far as I am aware, the facts and citations are accurate. But the ideas are poorly, and un-persuasively, expressed. I'll try to do better.

/false-sounding, but sincere, pouting

Post a Comment