Before the Administration or the Democrats conjure up a "compassionate conservative" update to HillaryCare, I wonder: Is there a crisis? (This post only peripherally touches upon whether government can best resolve any identified problem practically or economically.) Answer: As I recently concluded about poverty, the problem isn't half as bad as you might think.

- Scope of the problem: Especially for those considering legislating universal health care, the first step should be to determine how many Americans are uninsured. After all, any expanded system will generate increased tax-subsidized costs. The commonly cited statistic comes from the Census Bureau using 2003 numbers (Table 5): 45 million, or 15.4 percent of Americans lack health insurance (in 2002, 44 million or 15.2 percent). Seems simple? Not so--the data's both disputed and distorted depending on the speaker.

The Census numbers don't square with other figures--including data from other Federal government agencies. For example, the Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Disease Control, says 40.6 million Americans weren't covered in 2002, which they equate to 16.6 percent. CDC also has figures for the first nine months of 2004, which (Tables 1 and 2) show 42 million (14.5 percent) uninsured. With an important caveat, the Congressional Budget Office and the Joint Economic Committee side with Census. But what does that mean?: the Bureau itself publishes two different uninsured rates (using different methodology), prompting an avalanche of statistical debate over variances in approach and data collection.

Private sector numbers only add to the mystery. The Socialists, as well as the lobby group Families USA, say one-third, or 82 million Americans, lack health care. Kaiser Insurance company cuts that in half, to 45 million and insists the figure was only 40 million in 2000. The conservative Heritage Foundation uses, but disputes, the Census numbers. Governing, a monthly magazine for state and local government bureaucrats, drops the number to 43.6 million in 2002.

There's more. Cover the Uninsured Week -- a liberal lobby group advocating "health care coverage for all Americans" -- uses the same 2002 CBO data to argue that almost 18 percent of Americans are uninsured and 19 percent (or 18.2 million) adults with jobs (Table 5a) aren't covered. Given that most Americans' health insurance is tied to employment (Figure 1), this is, to say the least, suspicious. For its part, Reuters upped the figure to 20 million working Americans without health insurance.

Somewhat arbitrarily, let's say it's 16 percent and to hell with it. As shown below, it's not that easy. - Trend: Is health care coverage declining? Who knows? Governing magazine claims, "the situation continues to deteriorate. In 1992, there were 35.4 million uninsured people in the United States; a decade later, there were 43.6 million, with the biggest jump coming in 2001-02 when the rate rose 5.8 percent in that one year alone." The CDC says the increase was 0.4 percent; Kaiser agrees. CDC also notes, "The percentage of children uninsured during at least part of the past year decreased from 18.1% in 1997 to 12.5% in the first three quarters of 2004." Writing in the April 2005 Health Affairs, Todd Gilmer and Rick Kronick predict the number of uninsured will grow to 56 million by 2013.

Interestingly, insurance coverage is independent of the business cycle. The CBO compared 2002-3 data and concluded " the duration of uninsured spells has not varied much with changes in economic conditions." - Statistical Accuracy: All these numbers (including my 16 percent dartboard-selected assumption) still overestimate the coverage problem, for several reasons.

- Duration: The oft-cited Census numbers -- over 40 million/over 16 percent uninsured -- are only an instantaneous snapshot. As compared with Europe, America is less stratified and less regulated. As a result, and as previously discussed, we have substantial income mobility: poverty isn't permanent, reversals of fortune aren't pegged to winning the lottery, and today's uninsured are tomorrow's health care consumers: "According to the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, '[i]n the 1990s, over a third of people on low incomes escaped from poverty between one year and the next.'" On average, poverty is over within 4 to 8 months.

Health insurance coverage is equally fluid. Census Bureau data show (figure 11) that a family that loses health insurance is, on average, uninsured for only 5.6 months. Other government statistics differ, but all agree that long spells without insurance coverage are rare. The CBO concluded that the 40+ million/16 percent Census figure:overstates the number of people who are uninsured all year and more closely approximates the number who are uninsured at a point in time during the year. A more accurate estimate of the number of people who were uninsured for all of 1998--the most recent year for which reliable comparative data are available--is 21 million to 31 million, or 9 percent to 13 percent of nonelderly Americans.

As Dr. Devon Herrick observes, "That's far short of the 44 million often claimed."

Ephemerally Uninsured (Heritage)(click to enlarge)

Instead, the CBO's Lyle Nelson estimated only "about 30 percent of nonelderly Americans who become uninsured in a given year remain so for more than 12 months, while nearly half regain coverage within four months." From mid-1996-1997, CBO concluded about 84 percent of the uninsured were covered again after two years.

Coverage Interruptions (CBO)

The Joint Economic Committee read CBO data differently but consistently:one-half to two-thirds of Americans who experienced a period without insurance had coverage during some point that year. Additionally, the CBO found that more than three-quarters of the individuals who were uninsured at some point during a three year period (ending June 1999) were uninsured for less than 12 months. Only 6% were uninsured for more than 24 months.

Further, for the period January to September 2004, the CDC found that only 12.6% of employed adults had been uninsured for more than a year, rising to 32.8% of currently unemployed adults.

Kaiser Insurance disputed the government's figures, claiming (Figure 4) about 73 percent of the uninsured in 2003 had been without coverage for over a year; however, Kaiser never released its underlying data or methodology. - Overreporting Bias: Even static statistics of the uninsured exaggerate the problem. As the Senate Joint Economic Committee explained:

Estimates of the number of uninsured may be overstated. Methodologies for estimating the number of uninsured suffer from several shortcomings that may lead them to overestimate the number of uninsured. Many respondents are unsure of or forget their insurance status, which makes surveys tend to overestimate the ranks of the uninsured. Those eligible for Medicaid, in particular, may report themselves as uninsured even though they either have or could have Medicaid coverage. Indeed, fewer people indicate in surveys that they have Medicaid than are accounted for by the Medicaid program. Additionally, although many fail to formally sign up for Medicaid when eligible, their health care costs are still covered by the program since a patient can apply when they seek care and are covered retroactively.

The Census bureau concedes (Appendix C) it "underreports Medicare and Medicaid coverage."

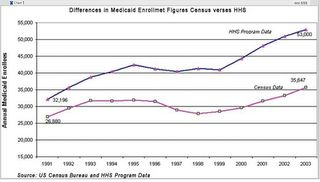

How much? The Heritage Foundation's Derek Hunter analysis showed an enormous swing:While the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) reported Medicaid enrollment of 51 million in 2002, the Census reported only 33 million, a difference of 18 million people. This trend continues in 2003 with a .7 percentage point increase in Medicaid enrollment by the Census Bureau, putting that number at 35 million, but CMS reports 53 million enrollees. This discrepancy is, to say the least, problematic.

Uninsured in Theory; Covered By Medicare in Fact (Heritage)

The effect of reporting bias on Census estimates is uncertain: Though CBO estimates the upward bias at 12-15 percent, another study claimed Census Bureau was off by only 0.2 percent. Without consensus, the public policy implications of overreporting are impossible to predict. - Uninsured Isn't Untreated: Even should 16 percent of America be uninsured, that doesn't necessarily imply enormous health risks nor appropriate government remedies. Many of the uninsured are relatively well off, suggesting they've intentionally forgone coverage. Census Bureau data shows (table 5) about 15 million uninsured in households earning over $50,000 annually. Cover The Uninsured calculated that 24 percent of Americans earning over $40,000 per year lacked health care coverage; Kaiser says that accounts for fully 20 percent of the uninsured (Table 1).

Moreover, increases in the number (as opposed to the percentage) of the uninsured are unrelated to government policy or the insurance market, as NCPA observed:The proportion of people without health insurance was about the same in 2003 (15.6 percent) as is was a decade earlier (15.3 percent in 1993). However, the number of people without health coverage increased by about 5.8 million people to 45 million, largely due to population growth.

Finally, the uninsured aren't untreated. Using CBO data from 2002, Cover the Uninsured found that over 80 percent of the uninsured had access to needed medical care for the past year (Table 6a). Dr. Samuel Zuvekas, Senior Economist at the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, calculates that (page 3) more than 60 percent of the uninsured retained a "usual source of [health] care." Though it's not ideal, hospital Emergency Rooms treat millions for "free", paid for by taxpayer-funded grants under Medicare Disproportional Hospital Share Program (see Table 4).

- Duration: The oft-cited Census numbers -- over 40 million/over 16 percent uninsured -- are only an instantaneous snapshot. As compared with Europe, America is less stratified and less regulated. As a result, and as previously discussed, we have substantial income mobility: poverty isn't permanent, reversals of fortune aren't pegged to winning the lottery, and today's uninsured are tomorrow's health care consumers: "According to the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, '[i]n the 1990s, over a third of people on low incomes escaped from poverty between one year and the next.'" On average, poverty is over within 4 to 8 months.

That don't mean the system's broken. U.S. medical care remains excellent. Many neither need nor want health care insurance: it's a gamble but that doesn't mean the state must overrule individual choice. The challenges are complex, as CBO recognized, "In considering any approach to expand health coverage, policymakers should be mindful of the fact that many people are uninsured for relatively short periods, whereas others are uninsured for much longer spans."

Some changes are necessary--particularly ending the tax code's linkage between health insurance and employment and scrapping the perverse incentive of providing free health care to illegal aliens, as BAH at A Certain Slant of Light plainly has demonstrated). But we can address those issues by tinkering, not replacing existing health care and insurance policies. So set aside that sledgehammer and conserve the good in what we already got.

2 comments:

Good blog, you seem to have a good one going here. Just wanted to leave a quick comment. Keep up the good work!

regards,

best health insurance california

cool blog have good statistics and explanation as well

Post a Comment