SECOND UPDATE: more replies and responses.

Third UPDATE: this thread continues here.

Guest blogging on SC&A, boomr properly pleads for reasoned debate. After that we part company--because he insists a new "centrist" party is the fastest path to civility and moderation. Below, I dispute some of boomr's analysis and recommendations.

- Party differences: Boomr wants it both ways, arguing Republicans and Democrats are different yet identical. First, he claims Republicans are "ruled by Biblical doctrine and by corporate bottom lines," while Democrats are motivated "by reaction to what the Republicans are doing and by social policies without focus." Next he insists neither group cares about "what may be the best thing for all the people in our country," and both favor "exclusion of other political voices." Though I disagree with boomr's description of Republicans, I'm certain both parties genuinely want the best for America and believe their platform would best achieve it. They just disagree about what's best and partisans (like me) think one approach superior to the other; boomr's differing characterizations (however inaccurate) demonstrate he too does distinguish.1

As for excluding other voices, boomr's point is either trivial (each party wants to win elections, and therefore exclude the voice of the other party's candidate) or flatly wrong regarding Republicans. It is Republicans and conservatives, after all, who favor debate followed by elections, where all voices may be heard and counted. By contrast, Democrats distrust the people and propel their platform via the unelected judiciary--thus narrowing the relevant voices from the hundreds of millions to nine.

Hey, look at me: a voice excluded by Democrats. Everyone's entitled to choose, but the parties are different. - Outlawing loyalty: Boomr blames the current acrimony on each party's insistence on loyalty. So boomr's proposed party would ban it, an idea with which MaxedOutMama appears to agree. The new group's "central tenent" would allow disagreements which, allegedly, will promote "benevolent compromise."

I have no objection, but it's either meaningless or impossible. Neither party suppresses opinions or debate on the latest questions.2 They do enforce party discipline once a policy is chosen (however accomplished). Why assume that's not "benevolent" or a "compromise?" On the other hand, if the centrist central tenant encourages members to undermine settled positions, boomr's new party will have a half-life measured in months. Boomr's approach creates a college-dorm bull-session, not an electable coalition. - A "No Religious Test" Test: I share boomr's commitment to religious freedom. The vast majority agree that certain entanglements between government and religion are unwise and unconstitutional. Normally, the government can neither force, nor prevent, church attendance. But that's the easy part.

Boomr's proposed party would be well more radical, "absolutely preclud[ing]" legislating based on "one group of citizens' idea of morality." This hostility to religious motivation, and his new leap to "morals," is neither explained, justified nor workable, as I've previously discussed. Neither law nor any proffered policy objective exclude religion from the public sphere, for example, on coins and in Congress. See, e.g., Walz v. Tax Comm'n, 397 U.S. 664, 671 (1970); Abington Sch. Dist. v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203, 213 (1963); Zorach v. Clausen, 343 U.S. 306, 312-13 (1954). Boomr's idea is unconstitutional.

And neither "religion" nor "morals" are easily defined. Take, for example, the "Golden Rule," which the various holy books require of Jews, Christians and Muslims. Would boomr's centrist party oppose laws that implement or further interpersonal reciprocity (say, for example, noise codes prohibiting sounds above a certain decibel level)? Would it matter if the lawmakers were "motivated" by the Golden Rule? If so, how would boomr propose to distinguish permissible and impermissible intent?

As another example, six of the Ten Commandments (see Deuteronomy 5:16-21) neither mention God nor any particular faith (e.g., "Thou shalt not kill."). And those six are codified as crimes under state and Federal law. Are such laws impermissibly "religious?" If not, are they unacceptably "moral?" If a legislator wants theft to remain a crime, is he imposing his religion or morals on others?

Boomr says a centrist party should "tolerate a range of ideas [and] morals." Fine. My idea is that adultery is immoral and hurts others (thus violating the Golden Rule). So suppose I favor criminalizing adultery.3 Would boomr tolerate my idea and morality? Or, as the late John Rawls once argued, are there "reasonable" and "ignorable" moralities? How could such a line be drawn? Wouldn't everyone draw it a bit different? That's not coherent, it's chaos. - Economics in the middle: Boomr's right about rejecting class warfare. But he's mostly wrong in arguing America needs a new "balance" between workers and business. That balance already exists, invented by Hayek and Reagan.

Despite widespread scorn for the "trickle down" economics, President Reagan was right that a rising tide lifts all boats, says Seth Norton in the CATO Journal:The incomes of the poor are intimately linked to the incomes of the rich. While the relationship is not one-for-one, it is notable. The incomes of the poor rise more with increases in the incomes of the rich than vice versa. More importantly, the incomes of the rich have a discernible effect in reducing the UN's conventional measure of poverty. Notably, growth in the incomes of the rich reduces the effects of poverty proportionally more than is the case for increases in the incomes of the poor. In addition, economic growth clearly reduces poverty. The results for sub-Saharan Africa are not appreciably different from the rest of the world.

Others agree that growth's the key to reducing poverty:

The term “trickle-down‚” is a misnomer: growth actually entails a cascade, not a trickle. The quality of growth may be important, but growth itself is the surest way to reduce human deprivation around the world.[A] recent World Bank study that looked at growth in 65 developing countries during the 1980s and 1990s. The share of people in poverty, defined as those living on less than a dollar per day, almost always declined in countries that experienced growth and increased in countries that experienced economic contractions. The faster the growth, the study found, the faster the poverty reduction, and vice versa. For example, an economic expansion in per capita income of 8.2 percent translated into a 6.1 reduction in the poverty rate. A contraction of 1.9 percent in output led to an increase of 1.5 percent in the poverty rate.

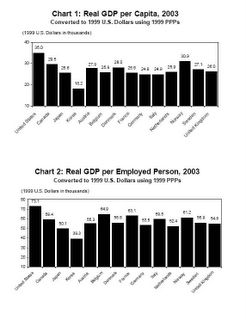

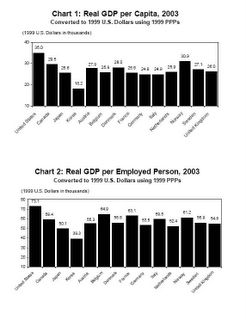

Data from the Bureau of Labor Statictics supports the notion that growth reduces poverty regardless of whether the rich benefit as well:

Comparison of GDP (click to enlarge)

Obviously, growth is good--even for the poor.

Now it's true that President Bush has departed from small government conservatism. He's wrong to do so--the recent Highway Bill, for example, should have been vetoed, not touted. But though Bush is off the reservation, there's widespread acknowledgment that "Reaganomics" -- also implemented by President Clinton beginning in 1995 -- strikes the appropriate balance, spurs growth and benefits all. - Campaign Finance Reform: This one's easy. We've had a belly full of reforms, which suppressed speech and were ineffective. By silencing individual opinion, banning "issue ads" is simply outrageous (as boomr recognizes). And Congress can't keep up with loopholes, as last year's "527" fiasco proved.

So repeal it all. Replace the morass with a simple concept: disclosure. Money doesn't necessarily corrupt--it mostly amplifies a speaker's, or an idea's, audience. And we can't stop the money anyway. But we can, and should, know about it. If Richard Gephardt, for example, is a wholly-owned subsidiary of the AFL-CIO, the voters can assess his candidacy in that light.

Make candidates promptly disclose the source and amount of every contribution (the FEC's computer system is nearly there already). Other than funding "coordinated" with a campaign (which fall under the above rule), private pressure/lobby groups must disclose the object and value of their spending (though not their contributors, see NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449, 461-63 (1958)). Such disclosure must be posted on the Internet within 48 hours. And, if -- as leftists imagine -- George Bush must paste a sticker on his forehead saying: "Property of "big oil" and Saudi Arabia," so be it. Why should boomr, or "the center," need more, especially (as boomr admits) where more chills speech?

It's a good effort. But few will join.

More:

Boomr replies; I respond.

Still More:

Another round of replies and responses.

_____________________

1 Addressing abortion, boomr suggests that the existance of pro-choice Republicans and pro-life Democrats demonstrates the convergance of the parties. Nonsense. The overwhelming majority in each party agree as to abortion. As an example, all candidates in last year's Democrat presidential primary supported Federalized legalized abortion. And former Pennsylvania Governor Bob Casey learned the costs of disputing settled Democrat doctrine. In any event, should abortion be the litmus test and lynchpin, the correlation would climb to about 2 sigma were the test rephrased as "favor retention of a judicially imposed absolute and unalterable Federalized Constitutional right."

2 I personally have observed this process within my party.

3 Supporting the criminalizing of particular conduct is not the same as supporting the agressive or intrusive enforcement of that crime.

8 comments:

Excellent post- we are going to discuss this later on.

Very well done.

Good response, boomr; a few brief reactions:

1 & 2) Party differences and loyalty: Although I agree that both parties oppose creating another, that has little causal connection with the absence of any viable third party. The real reasons are "first past the post" elections (everywhere except Louisiana) and the Electoral College system in Presidential elections. Both approaches implement "winner take all," thus discouraging more than two parties (and incidentally discouraging coalition government). The Electoral College was designed by the founders to discourage "regionalism" (meaning multiple, but only regional, parties). The parties aren't permanent -- Republicans arose out of the ashes of the Whigs, Whigs from the Federalists -- but, for better or worse, America's voting system sacrifices the old in the face of the new.

One can debate voting systems endlessly, but Ken Arrow won a Nobel demonstrating that every voting system is flawed. But it is voting systems, not the present parties, that block your vision.

I don't think you've rebutted my claim that Republican party policy is more amenable to debate and voting than Democrats. I'm not sure either group "suppresses" minority opinion in any non-trivial way (see, e.g., Ted Kennedy and John McCain in the 1980 and 2000 Presidential primaries). Debates are a contract between candidates and the media, not state action. Party "whips" do herd cats, once the majority view is clear. And, of course, majority views change (e.g., the Dems' reversal on free trade). Partisans -- like me -- know they won't agree universally--but make a constantly re-assessed calculation of what best advances their interests. This is neither corrupt nor a compelled check on a Congressman's conscience. See, e.g., Senators Jim Jeffords and Phil Gramm. I don't know whether that's equivalent to your 90%/10% ratio, but submit that such assessments are part of each party member's conscience, and cannot be externally imposed.

Even assuming the parties are equally guilty in "suppressing" third parties or minority opinion, do you dispute that Republicans, on the whole, favor letting the electorate settle many more issues than do the Democrats? What's your evidence? You seem to violate your own proposal, below.

Sorry 'bout the typo; thanks.

3) Religion: The flaw in your argument is defining "religion" and "morality" as you see it. You're picking and choosing to fit your doctrine, not reflecting another's religion or morals. I have no idea whether prohibitions on theft, lies, murder, etc., predated Moses. But, I submit, neither do you: plenty of societies today permit at least some murders (honor killings) or institutionalize theft (the "jizyah" tax on "people of the book"). How do you distinguish between morals that "originated in the very foundations of society" from others? Is there a time in human history "before religion was even established?" (and, if so, why is that the sole starting point?).

You attempt to deploy "hurt" as a deus ex machina neutral principle. But it's not neutral--unless you believe the founders intended America be a Judeo-Christian country. Absent that, people will differ on what hurts, and what they would outlaw. Why is your view superior? Surely you're not basing your system on the notion that adultery doesn't hurt--it did and does. (Are criminal sanctions against suicide unlawful?) And I know what Thomas said--but why would you forbid enacting societal standards but tempering enforcement? I don't think it "irrelevant." Why is that middle ground unavailable to a majority? Where does it say that in the Constitution.

Again, assuming (what I presume is your view) America's laws need not necessarily reflect Judeo-Christian ethics, there is no neutral principle of appropriate beliefs or acceptable morality. Instead, our representative democracy chooses its laws via elections (November votes, and Congressional yeas/nays). The sole limitation on the will of the majority are those minority right protected by the Constitution. And, outside of particular protections in the text (e.g., the First Amendment's application to obscenity), the Constitution does not prohibit legislation founded on the majority's morals. Nor does it forbid choices some think stupid--or irrelevant.

Further, you still provide no practical way to distinguish between the impermissibly "religious" and the acceptable "foundations of society." If a state legislature doesn't say "because the bible tells me so," but nonetheless bases support for a law on their Judeo-Christian worldview, is criminalizing theft Constitutional or not? How do you propose interrogating the subjective opinions of Congress? Or the electorate? How can you imagine either is Constitutional?

You give the game away by supposing some universal, but non-religious, code of morality. You transgress logic again by a personal, and constrained, definition of hurt. In the guise of religious neutrality, your approach merely locks-in your brand of liberal secularism. That's fine--if you get the votes. Otherwise, you're only acting as you claim you abhor: preventing debates and votes by subordinating the "appropriate" to your dictates.

4) Economics: Your approach appears to be grounded on the notion that there is some "right" balance of salaries. I know of no such thing. In any event, in addition to individual merit, salary is a product of demand. To the extent they choke profits, salaries will drop; if revenues rise, salaries may too. So long as executive salaries are fully disclosed (to shareholders, bond holders, the Board, i.e., the public) salaries will vary over time, with a trend toward the mean.

And I see no evidence today's workers are more impoverished. Indeed, I've shown the opposite.

5) Campaign finance: Where's evidence of the excluded voiceless? Between Nader and the "527s," money made possible more opinion than ever. And there's a Washington lobby for every "special interest"--or two or three. What's the problem with that? Given the widely acknowledged division among the electorate, do you really think campaign finance corrupted anyone? (Bribing voters is, and should remain, unlawful.)

Even were forbidding money consistent with the First Amendment -- and it ain't -- your approach would leave the media as the sole "uncoordinated" speaker. How could that be desirable?

Conclusion: Obviously, I don't object to your plan to create a new party. I do oppose most of your economic and campaign law tinkering. And I'm convinced your anti-religious test and some of proposed election reform are unconstitutional. But, outside those areas, I'm not advocating suppressing your voice. Instead, let the best idea win: not by personal or judicial fiat, but by simple numerical majority. That's how we settle disputes in America.

Pictorial evidence of adultery's "hurt."

boomr:

I think we're talking past each other. In order of importance:

1) Constitutionality of morals legislation: You say "Show me where it's allowed," which reflects a gross misunderstanding of the Constitution. Bluntly, you've erroneously reversed your burden of proof.

The Constitution grants limited Federal powers, reserving all other powers to the states and the people. Yes, the Constitution forbids some narrow sorts of state action (infringing on now-incorporated Bill of Rights provisions, departing from those Amendments directed toward state action (e.g., the 15th Amendment) and (under the supremacy clause) trumping statutory preemption that itself derives from a lawful Federal power.

In arguing "anything not listed is prohibited," you've fundamentally misread the Constitution (especially the 10th Amendment) and its entire intent. (Indeed, you seem to have lapsed into East German-itis.) What you say is true only for the Federal government. In contrast, each state is a separate sovereign; the scope of state power does not derive from, and need not be tied to particular language in, the U.S. Constitution. Apart from the previous sort of textual limitations, states may do anything. The fact that neither morality nor the lawfulness of morals-based legislation is not mentioned in the Constitution confirms states have the right, power and authority to enact morals-based legislation. Whether they choose to do so is a question for each state' citizens and their elected representatives.

2) Religion: You insist on picking and choosing what you consider religious, and your definitions are wrong, inconsistent, and not widely shared. For example, you avoid the religious basis of the 10 Commandments by pointing to an earlier, and somewhat similar, compilation. I do appreciate your reference to the Code of Hammurabi, which indeed predated Mosaic law. But that doesn't make the Code any less religious than the 10 Commandments, as demonstrated by just the first paragraph of the preamble to Hammurabi's code:

"When Anu the Sublime, King of the Anunaki, and Bel, the lord of Heaven and earth, who decreed the fate of the land, assigned to Marduk, the over-ruling son of Ea, God of righteousness, dominion over earthly man, and made him great among the Igigi, they called Babylon by his illustrious name, made it great on earth, and founded an everlasting kingdom in it, whose foundations are laid so solidly as those of heaven and earth; then Anu and Bel called by name me, Hammurabi, the exalted prince, who feared God, to bring about the rule of righteousness in the land, to destroy the wicked and the evil-doers; so that the strong should not harm the weak; so that I should rule over the black-headed people like Shamash, and enlighten the land, to further the well-being of mankind."

Ah that clever, secular, Hammurabi!

To the extent you claim the code is not only non religious but also a just and an appropriate foundation for modern law, I note that Hammurabi code also provides for trial by compurgation (clause 2), limits on the alienability of property (clauses 36-38), slavery (clauses 7, 15 and passim) and, unsurprisingly, criminalizes adultery (clause 129-30):

"129. If a man's wife be surprised (in flagrante delicto) with another man, both shall be tied and thrown into the water, but the husband may pardon his wife and the king his slaves.

130. If a man violate the wife (betrothed or child-wife) of another man, who has never known a man, and still lives in her father's house, and sleep with her and be surprised, this man shall be put to death, but the wife is blameless."

Simply put boomr, Hammurabi doesn't help your case. Either a) Hammurabi also is both religious and based on morals (therefore disproving your notion that morals and religion are easily distinguished); b) there are no universally agreed upon laws/principles/codes that "originated in the very foundations of society before religion was even established" and were part of "the basic social compact OF EVERY SOCIETY, EVER;" or c) prohibitions on adultery (and possibly other enumerated practices) are included in "the basic social compact OF EVERY SOCIETY, EVER."

Criminalizing blasphemy is easy--it would violate the First Amendment. But your proposed test flounders on anything more complicated--public school Christmas carols, for example. And you've made my point regarding legitimate state interest/rational basis: again, assuming no overt religious references in law or legislative history, statutes may be motivated by a religious worldview--and still be legitimate, rational and Constitutional.

3) Morals: Your reliance on utilitarianism as the sole acceptable touchstone for law and your selective definition of morality lead you to numerous errors. First you claim law can't address "sadness," but may "protect society" only when necessary to prevent "hurt." This is neither mandated by the Constitution nor practical. How much "hurt" qualifies a practice as criminal? Sadness sure hurts. I say adultery hurts; its victims are both the cuckold and the society. You disagree, fine. But what gives you the right to choose the categories and their definition?

(And, by the way, stealing is always immoral and always criminal; mitigation based on context goes to sentencing, not guilt. The fact that stealing also is economically inefficient merely demonstrates the difficulty one has in identifying morality under purely utilitarian analysis, as J.S. Mill understood. Moreover your analysis of "selective enforcement" -- which is to say, prosecutorial discretion, a concept having no connection to Article IV or Amendments 4, 6 and 8 -- is flatly false. See United States v. Armstrong, 517 U. S. 456, 463-65 (1996); Wayte v. United States, 470 U.S. 598, 607-08 (1985).)

Second, even assuming a utilitarian approach is required, who decides? How do you distinguish the two? To coin a phrase, who died and made you God? Do you actually believe the outcomes of your assessments are infallible? Or universal? I assure you, your categorizations are not. And we've not even addressed polygamy!

Even liberals split on whether prostitution is immoral or should be criminalized. Why are you right? Why should your views prevail over the assessments of others?

Conclusion: The Constitution does not enshrine your on anyone's particular morality or faith. But neither does it mandate your morals or beliefs. Not everyone would sign on to my views; I, for one, oppose yours.

How does the Constitution resolve such disputes? Well, government can't transgress the Bill of Rights, which outlaws establishing any one faith or inhibiting another (subject to various exceptions not relevant here). But beyond that, what's the Constitutional process for choosing sides? Simple: elections.

The Constitution contains no shortcuts--and certainly none that codify your assessment of appropriateness. Though your way may be better, the 10th Amendment gives us the "right to be wrong"--and the concomitant ability to change our minds next November. So if you want to eliminate morals-based laws, "abandon [your] tautological and un-democratic slight-of-hand. Fight like an American: put tolerance to a vote." And this time, persuade more than 48 percent.

Boomr:

1) Conflict between Free Exercise and Establishment: Yes there is one. I admit it. So does Justice Ginsburg. And, remember, we agree on the unconstitutionality of legislating religion. Where we part is your insistence that we can (or must) identify and prohibit religious views shaping laws, either practically or Constitutionally.

2) Legislative justification: We need not, and I will not, debate what hurt is sufficient (resulting from, say, theft or adultery) to justify legislation. My point is that reasonable people will disagree on the topic, as you disagree with me. Never mind trying to convince me any particular act causes insufficient hurt, the real point is why should your view exclude mine? Where is that authorized in the Constitution?

I have no idea what you're saying about Hammurabi. You cited that code to argue that prohibitions on, say, theft predated Moses. We agree they did. But how does that help you since the prohibition you mention also was religious?

3) Morals as justification: You said your new party would favor "absolutely preclud[ing]" legislating based on "one group of citizens' idea of morality." But, mandating your definitions, you're doing exactly that! Again, that's why we have elections. Which you seem to recognize when mentioning President Goober.

4) Morals as Constitutional: I said the Constitution doesn't bar legislation based on morals. Your reply addresses "religiously-based legislation," which I did not say. This shift reflects your repeated slight-of-hand insisting that you be able to define what's moral.

Your Constitutional interpretation remains wrong: the sovereign states came together to devolve some sovereignty to the central government, retaining all other aspects of sovereignty. Your 14th Amendment is similarly circular: it has been read to incorporate the Bill of Rights protections, which say nothing about morals. This is shown in your assertion that states may not act in a fashion "MORE restrictive to an individual's Constitutional rights"--it's correct as far as it goes, but individual rights are specified in the Constitution, which doesn't address morals. Again you argue moral-based legislation is bared because it infringes civil rights, but only by assuming that the Constitution establishes a prohibition on moral legislation.

Same with your ending. Constitutional rights -- such as laws solely aimed at one's soul -- are not subject to votes. But stop reading "religious" for "morals" and quit assuming the conclusion.

5) Selective enforcement: Yes, the rule is that the selectivity cannot infringe a right guaranteed under the Constitution. Enforcing criminal laws only against blacks is barred by the 14th Amendment. But that rule applies only to rights protected by the 14th Amendment. Circular again. (And, by the way, your Article IV argument makes no sense: criminal laws don't apply outside the sovereign state (with trivial exceptions). And full faith and credit applies to governmental acts, not to inaction.)

Good debate.

Boomr, you are arguing in your second-to-last that religiously based morality can't be distinguished from other morality. I agree. Morality is distinct from religion. Both dedicated atheists and religious people often make the same moral or ethical arguments.

Furthermore, ethics is distinct from morality. I may (and I do) believe that adultery is extremely harmful and morally wrong yet I also believe that most laws outlawing adultery are unethical. I do so on the moral principle that no law can be ethical if it causes more harm than it prevents, and that in most cases public punishment of this misdeed creates more harm than it prevents.

But if morality is not necessarily integral with religion, then how can you possibly argue in good faith that a particular ethical rule may not be enacted into law based on the majority of the voting individual's moral judgments (whether associated with a particular religion or not)? Your argument appears to defeat itself.

Also you are misrepresenting the First Amendment when you write:

"The document doesn't just prohibit the establishment of "any one faith," but of any law "respecting" ANY FAITH, whether that's one faith or many."

The text of the 1st Amendment reads:

"Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof..."

How do you derive your interpretation? It does not coincide with the text of the first amendment. "make no law respecting an establishment of religion" is quite a different prohibition than "prohibit any law respecting ANY FAITH". Prohibiting an establishment of religion is clearly meant to ensure that no one religious organization can be given an official position in our society.

Under the circumstances I am coming perilously close to suspecting you of using a deliberately disingenuous wording here. "Respect" as used in the first amendment means "with regard to or having a relationship with". As used in your interesting reframing of the First Amendment, the word could easily be understood as "giving credence to or recognizing".

To put it bluntly, saying that a person can't vote their personal ethical convictions would be a prohibition of free exercise of the individual's conscience. For some individuals, this might be tied up in religion. For others it wouldn't be. All your arguments seek to disadvantage some moral principles that you consider religious and advantage some others you consider to be non-religious, but you get to pick which ones are invalid. This is the most flagrantly anti-democratic idea I have ever encountered.

Even the courts have consistently recognized atheistic/secular moral principles as having the same status under law as religious moral arguments. So for instance, the conscientious objection exemption from the draft can't be restricted to the religious nature of the objection.

You seek to grant or deny rights of exercise of conscience based on whether, in your judgment, a particular conscience has been influenced by religion as opposed by ethics. This is exactly what the Supreme Court has ruled invalid (even though they do it themselves). That cannot be the criteria under the American Constitution.

Please rebut my criticisms or restate your argument so as to invalidate them.

boomr:

Am I mistaken, or are you a libertarian?

I've replied in a new post here; please post future comments on that page.

Post a Comment